How LGBT peoples' lives have been changed by the internet

|

|

The experience of changing the username of my federated login got me thinking about how the internet has affected the lives of LGBT people. |

|

What does LGBT mean? It stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender. You often see it extended, perhaps with: I for Intersex, covering many biological conditions which are associated with not physically matching binary ideas of a single gender Q for Queer, a term of abuse that has been reclaimed And my favourite, LGBT+ |

|

One of the first big political campaigns for LGBT rights in the western world was decriminalisation. The most recent big one is marriage equality. We can learn a lot by comparing them. In Ireland, there's a cliché that if you ask for directions, someone will tell you "Well I wouldn't start from here." That's how it was for LGBT rights 30 years ago. Gay people were still criminalised in Ireland, and this was reflected in the media. Any kind of mainstream access was very difficult to get, and who knows if you'd get a sympathetic or even reasonably balanced hearing. If you can't get coverage in your own words, then it doesn't matter how watertight your arguments are. You can't reach anyone. |

|

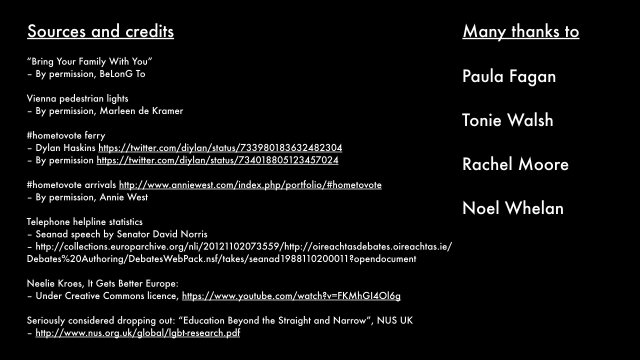

Now we have things like this beautiful video by BeLonG To. This sort of thing doesn't need to be on TV. It got enormous coverage just by being shared on YouTube. The big message is that we can't win this on our own. We need the support of our families and friends. And when you talk, you win people over. Video credit: BeLonG To, by permission. |

|

You know you're mainstream when they change the pedestrian lights in Vienna. My friend Marleen took these photos and she said that there was a politician who wanted to complain about them, but of course he wouldn't complain about supporting LGBT rights. No, he complained about the cost of doing this, isn't it wasteful? And his counterpart in the Green Party agreed! And said "Ok, you're right, let's not spend the money to take them back down." Photo credit: Marleen de Kramer, by permission. |

|

But a broadcast-style campaign isn't enough. To change peoples' minds, you need to speak with them directly. The way canvassing usually works is that it's organised by political parties. At local level, this means a politician's secretary ringing around, trying to find out who'll go out tonight. But there was something different about marriage equality. |

|

I spoke to Noel Whelan, who's very politically experienced and got involved in the Yes Equality campaign in Ireland. He said that the LGBT community were engaged intensely, not just canvassing, but following every single utterance of the campaign. "There's never been a level of internet engagement with opinion as there was about the marriage referendum." Twitter activism is one thing, but you can harness that engagement, and they did. Noel described the Yes Equality campaign as a "pop-up political machine." Instead of a politician's secretary ringing around, it became "We'll meet at 18:30 at this public house on a Tuesday..." Everything was set up to make it as easy as possible for inexperienced but eager people to get involved. The front page of the Yes Equality website was basically a Google Spreadsheet telling people "If you want to canvass in this location, phone this person and be at X place at Y time." |

|

"Oh, and watch this video about how to canvass before you leave." Which works great - IF you're addressing the concerns people really have. |

|

So pre-internet:

So you can't make your arguments, you've no way to get feedback on them, and you've no way to adjust them. Vestiges of this remain. Mainstream media, especially state broadcasters, often have some sort of mandate to be impartial. That's a difficult thing to do. So they will sometimes fall back on a 50/50 rule of broadcast time for both sides, which is a sort of "documentably" fair. But it has weird effects; imagine giving 50% of time to an anti-climate change argument. The big worry with a referendum like this is that, since it's about something where the majority of people aren't going to get a direct benefit, the smallest of doubts can flip people around. There's a whole menu of doubts getting 50% of time on the media. Which ones are actually shared by voters? |

|

We now have:

...and they're all on Whatsapp! The pop-up campaigning machine worked both ways. Noel and the organisers could see canvassers reporting back in, and that told them that, while the debates were getting coverage, they weren't moving opinion. |

|

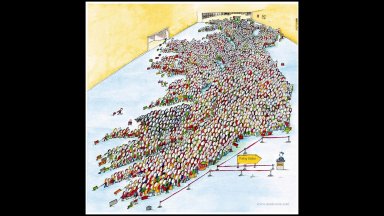

And then, on the day of the referendum, something happened that nobody expected. In Ireland, you can't vote from abroad. But if you haven't been away too long, and you're still on the register - you can come back. And people did, in droves. |

|

Twitter filled up with photos of people on planes, on trains, on ferries. Like this one from Dylan Haskins.

Photo credit: Dylan Haskins

@diylan |

|

Colm O'Regan said this. |

|

Annie West drew this.

Image credit: Annie West, by permission. |

|

Community is important. John Dyer, on Monday, said "Projects come and go, what endures is community." But to talk about community, first I need to talk about labels. |

|

Sometimes I have conversations about being LGBT, and someone pipes up with "Why do we have to have all these labels? Why do we all have to be straight or gay or whatever? Why can't we just be people?" Because labels are the mechanism by which I identify my needs which are different from someone else's.

Having labels forced on you, that's a problem. But if I can't describe myself, then I can't find my community. Tonie Walsh, curator of the Irish Queer Archive in the National Library, said that community is where people "address their fears, imagine their desires and quantify their needs." |

|

Pre-internet, this broke down three ways, and the big deal was how fragile these three things are. They can all come under attack, accidental or deliberate. |

|

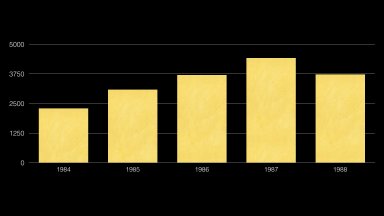

The Irish telephone helpline was getting 10 calls a day in the 1980s - that's a lot for a volunteer service in a country of that size - and it increased until 1988... which is when the physical centre caught fire. Source: Speech from Senator David Norris So without the physical centre, and without the helpline, and the mainstream media won't even take ads for meet & greets - you're down to independent newsletters. Which the government tried to ban. There's nothing wrong with being LGBT. But we soak up the same messages as everyone else does, so discovering this about yourself can be difficult. You need to get support. When the support infrastructure is this fragile, that's a problem. Depending on who and where you are, it still is. |

|

Dan Savage's idea, reacting to suicides of LGBT teens in the US, was to record a video with him and his husband, telling people - it gets better. And he encouraged others to do the same. Apple employees, Google employees, Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and... |

|

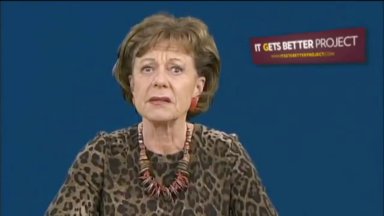

Neelie Kroes. It's worth hearing her own story of discrimination, as a woman. So, have things gotten better? How are things in our own community? We are networkers. We measure things. What numbers can we get? Let's look at student dropouts right. If they're higher for LGBT people, then we can see that something is going on.

Video credit: Neelie Kroes, under Creative Commons license. |

|

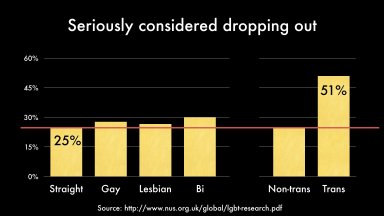

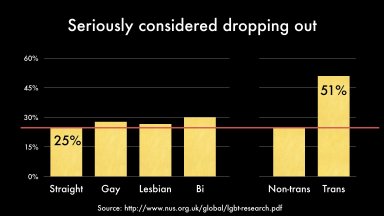

The National Union of Students in the UK did a survey about two years ago. They discovered that 25% of straight students seriously consider dropping out. So that's our baseline. For gay students, the number is 27.7%, which looks like a small increase, but it's about 15% higher. For Lesbian students, 26.6%. Bisexual students it's HIGHER at 30% - there's something going on that affects bi students in a way that it doesn't affect gay and lesbian students. For trans students - and comparing "trans" to "straight" is not correct, the report is sensible enough to compare to cisgender, where the numbers are similar - the number is over half. This is the community we serve. |

|

And it comes back to identity. This is really core. Who am I? We all experience these pressures - LGBT people perhaps more than most, but everyone does. My own story is that I spent 40 years learning to be male, and now I'm unlearning that. How do you do something like that? |

|

I spoke to Rachel Moore, founder of eXpress Your Gender. She looked at the advice out there and found it… lacking The worst was prescriptive, based on stereotypes. The best was… only okay. But she notice that it tended to be based on observation. which surprised me. Don’t we already know how men and women work? We think we know! But these are ideas that have arisen long ago, and are reinforced through how we interact with the world, in media, and they don’t really represent reality. Rachel told me that she believes this doesn’t just apply to trans people, or non-binary people, or LGBT people. We are all exposed to these pressures and assumptions every day. But the research out there is not great. So what can you do? |

|

Rachel’s developing something. It starts with this site. |

|

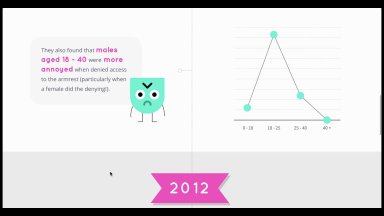

She’s gathered a bunch of good observational data that’s already out there. |

|

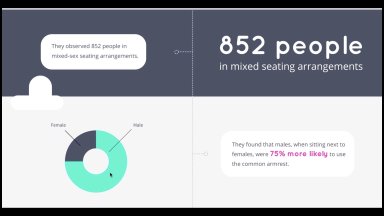

The thing about men hogging the armrest, is it true? |

|

Turns out, it is! But the existing studies are limited, like Rachel said. So what can we do about that? Source: "Sex and the Single Armrest" Dorothy M. Hai, Zahid Y. Khairullah, Nancy Coulmas. Psychological Reports, 1982, 51, 743-749. |

|

She’s also developing a forum. |

|

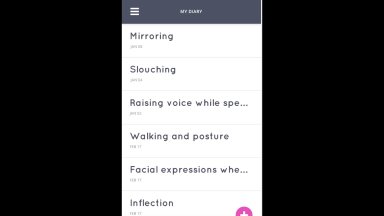

This isn’t launched yet, this is developer examples, but Rachel’s whole thing is to get real observations done. But the problem with observations is, in the past, to get good data you’d really have to set out to do it and note things down to log when you get home. But now we have mobile phones. So along with all this, Rachel’s developing an app. |

|

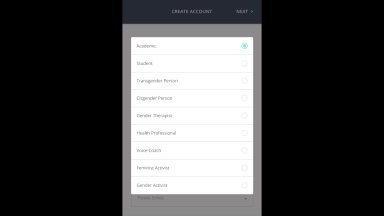

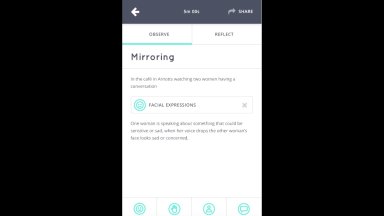

So you login, and tell it what kind of user you are. Then you can just go for a coffee, or waiting at the train station, start making observations. |

|

It’s not just like a pencil and paper - the app is guiding you in making objective observations. Log what you actually see, not what you think is going on. |

|

You write your observation |

|

And submit it! Isn’t that cool? We all know, you can’t change what you don’t measure. There’s something really interesting going on when we carry around little pocket supercomputers. I wear a watch that measures my heart rate and could let me participate in medical trials. And this sort of thing — there’s been a barrier to getting real observations that’s just now starting to crumble. Rachel firmly believes this isn’t just for trans people either. We’re all vulnerable to these messages, these pressures. And the difference is having access to this information. Discovering this unsatisfaction - that gets you maybe 70% of the way. But then you’re stuck! What do you do? Having access to real, observational information could make that difference. |

|

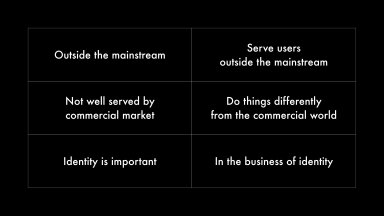

So that's identity. So what's this got to do with us? Well, let's look back at what we've seen. What needs do LGBT people have? |

|

The needs of the LGBT community and the things that NRENs are good at look remarkably similar. We're in the business of identity. So how do we do? |

|

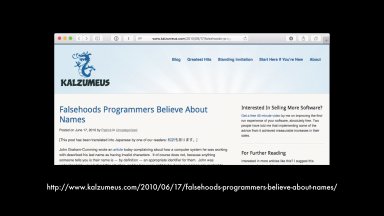

This is a page called "Falsehoods programmers believe about names". Some of my favourites:

|

|

Which gets even more fun when you get to falsehoods programmers believe about gender “A person has one legal gender that is consistent across all their forms of identification.” Source: Falsehoods Programmers believe about Gender I've been called brave for lots of reasons. As a visibly trans person, I've been called brave for walking down the street. I've been called brave for coming out at work, and transitioning at work. I get called brave all the time for standing up and giving presentations. I have a funny relationship with that word, because in many ways I'm just on my journey and you're on yours and we all just overcome things as best we can. But perhaps the most valid was this: I was brave for trying to change the username of my federated login. |

|

I don't want to pick on the federated identity part of our community here, because what I'm getting at affects us all. We are building infrastructures around majority use cases. All of us find ourselves spending a bit of time outside the majority - when we need to log on to the provisioning system from our phone over 3G instead of from our desktop PC inside a firewall. On average it works out. But averages are misleading. If the average works out, most people work out most of the time. But for some people it works out almost none of the time. We make assumptions like "a person's username isn't going to change" and then that assumption leaves me with a choice:

Assumptions like "a person's name doesn't change very often" was perhaps even worse for me for a while. For an extended period, my name would change when I left the office. There were people in my life who only knew me by my old name, and others who only knew me by my new name. What's my "real name" in that situation? It's very hard to thread that needle without disclosing both your names, and now it's not just about your name, because now you're having a conversation about your gender identity and labelling yourself with a particular minority status and it has been forced upon you. Even my bloody iPad betrayed me! I changed it to "Anna's iPad" a few months before I transitioned in work, then joined a videoconference with it; I didn't realise it was displaying the device name at the remote end until someone said "can you not get your own iPad?" |

|

Changing my username went remarkably well. I had primed people to expect it, so there were preparations in place, and I knew who to contact if things went wrong. Which they did. But I was only out of action for about 45 minutes before I got some access back, and then the rest of the problems were mostly cleared up over the course of the day. By that measure - that's a big success. The number of work hours lost was very small. But. This was a best case scenario. I had a tradeoff I had to manage - I wanted the gap between disclosing to my colleagues and actual transition to be short. But to prepare for a change like this, you want the distance between decision and action to be long. So I had to work with my old username for some time after transition. More importantly: I'm on a first name basis with everyone whose help I needed to make this work. As soon as something broke, I was either at someone's desk or I was firing off emails or phone calls to someone who could sort me out. It was done quickly, but it still took a number of iterations. If I had to go through a university helpdesk, and then through an NREN helpdesk, and THEN through a third party helpdesk - and back - for every one of those iterations - all while going through a very significant and emotional life change - I might decide that it's just not worth the effort. But maybe it's ok. Maybe it's not worth the cost to engineer for the minority. It sucks to be them, but I mean, only a very small minority of people ever change their name. Like trans people... |

|

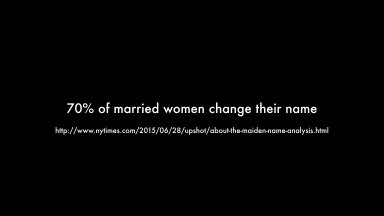

...oh, and married women. The thing about designing things to be accessible is that it benefits everyone There's a concept in accessibility called universal design. It's about getting away from the idea of just adding wheelchair ramps. If your corridors are wide and step-free, then it doesn't just help wheelchair users, it helps you when you're carrying something heavy. If our systems accommodate the LGBT community, that helps everyone. Let's look at those dropout stats again. |

|

What can we do about this? |

|

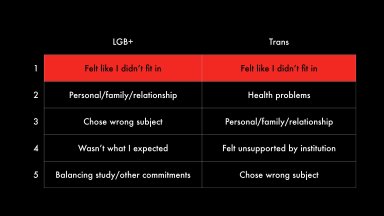

Top of the list: not fitting in. …why is that? Rachel’s met a LOT of people in college, or who used to be in college, and can’t get access, can’t get their transcripts changed. Some had their email name changed, but not their username. And that can be really painful. Why? We think of usernames as a mostly-hidden field. “Just make an exception when it’s needed.” If I go into class, the lecturer has printed off a class list to call the roll. If that name is wrong, the lecturer is going to read John instead of Mary. How are you going to excel in a college environment if stuff like this is your biggest priority? On the flip side, it really helps people to be taken seriously if they know the college is backing you up. When I transitioned in work, I took one of our large clients’ gender identity policies with me to the meeting, to show: this is something our community takes seriously. So what can we do? When we put systems in place, those systems get used in ways we don't expect And they are inflexible. That means it's on us. Not just that we CAN make a difference - for the stuff we do, we're the ONLY people who can make a difference. And we make some boneheaded decisions sometimes. Not because we're idiots, but because we don't know how this stuff will be used. So we make assumptions. Decisions are being made this week that are hugely important to LGBT people. How do we not screw this up? |

|

There are some obvious things, like gender boxes, and taking a bit of care with what we ask - do you really need to know someone’s gender? Do you really need to ask for their legal name? Example: UK Government Service Design Manual But I can’t write this manual for NRENs. I don’t know your work. Besides. Who comes here to get more work to do? Steve Cotter and Kees Neggers gave us the answer on Monday: we need to listen to the needs of our users. |

|

This is the manual. The people in this room hold huge power in affecting a student’s daily lived experience, even whether they drop out or not. And we already know how that affects someone’s entire life – If someone drops out, you’ve got depression, social isolation, “there’s no place for me in this world,” “no one’s going to want to employ me” - and it affects someone’s long term outcome to the point where they might be on long term benefits, even suicidality. We can have an impact on these rates by making recognition of gender identities and LGBT people a priority. But every time we go "that's an exception", we force a call through the chain of helpdesks, and we lose a percentage of those requests. Because there's only so many times you can justify your identity to a busy person on a helpdesk whose job requires them to fit you in box. |

|

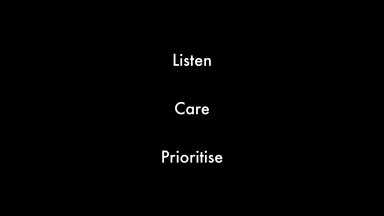

Ann referred to this graph on Monday. It showed us that we serve all the users, from the most mainstream to the most demanding. Doesn’t just have to be bandwidth. Our very structure, most of us being nonprofits, reflects that we work for our communities. It’s not just that we CAN make a difference to the LGBT community. It’s that for the particular work we do, we’re the ONLY ones who can make that difference. |

|

I can’t write the manual because I don’t know your work. All I can do is tell you a little about this community. But you don’t have to stop here, with this talk. This journey has been immensely fulfilling for me. The number of smart, insightful people out there who have something to say is – it's been the greatest privilege of my life. And you don't have to be LGBT to enjoy that. The more you learn about the LGBT community, or the communities the next speaker will talk about, the more it helps our work, and the more it helps our own selves, gay, straight or otherwise. |

|

|